Hi.

OpenArt is an independent curatorial art media platform. Publisher of [soft] artist interview magazine.

OpenArt is an independent curatorial art media platform. Publisher of [soft] artist interview magazine.

Name: Lin Wang

City: Oslo

Website: https://linwangart.com/

Q: When we met again in Jingdezhen last time, I found your recent work especially intriguing. There don’t seem to be many Chinese artists living in the Nordic countries. I’m curious about your life there. What brought you to Norway to work as an artist?

When I was young, I was passionate and believed in romance. I met someone and followed them there. Initially, I wasn't even in Oslo, but in Bergen, Norway's second-largest city, which felt like a small fishing village to me. I came to the distant Nordic region chasing love, and my exotic dream began from there.

After I arrived, I was in a state of cultural shock, compounded by the polar night. I remember arriving around September or October, when the days grew darker and darker, and after it got dark, it never got bright again. I had no friends, and I think I became depressed. I was depressed for three months, just crouching in the bathroom, sitting there unable to leave the house, feeling extremely depressed.

Later, I thought I should stop worrying about art and focus on saving myself first. I started running, running down from the mountains, then jumping into the sea, and running back. At that time, I couldn't make art at all; I could only think about how to survive, how to adapt to the weather, food, and unfamiliar environment.

Gradually, I began making lamp-like objects. Having never experienced the extremes of Nordic daylight and darkness, the long nights felt overwhelming. So I made sculptural lamps, almost as a way of pulling myself back into the light.

To me, that’s what contemporary art is: solving the problems you’re facing right now. Living in the Nordics, there’s no shortage of challenges — which means there’s no shortage of inspiration. My language skills weren’t strong either; I could only manage basic English and couldn’t express deeper ideas. Plus, I was already quite old when I went there, having graduated from university.

Later, the romance inevitably fizzled. The cultural differences were just too big. So I went back to school. After graduating, I was broke — but I was desperate to bring my ideas to life. I wanted so badly for my graduation work to be understood that I poured everything into visual expression. I went into a frenzy of creation.

Exotic Dreams and Poetic Misunderstandings Project-The Maritime Silk Road (2016)

Q: What was your graduation work like? Does it connect to your current pieces?

It’s all connected. Back then, I desperately wanted to be understood — and I also wanted to avoid small talk or feeding into people’s exotic fantasies.

As a young Asian woman in Norway, it was easy to attract the attention of older men who saw me as “exotic” or easy. People following you around might be because of their imagination about Asian women. But I felt I had far more to offer — and I certainly didn’t want to play into anyone’s fantasy. I wanted to express my own reality.

Art felt like the strongest language I had. And visual language worked best — because even if you speak someone’s native language fluently, it’s still not always possible to express yourself precisely.

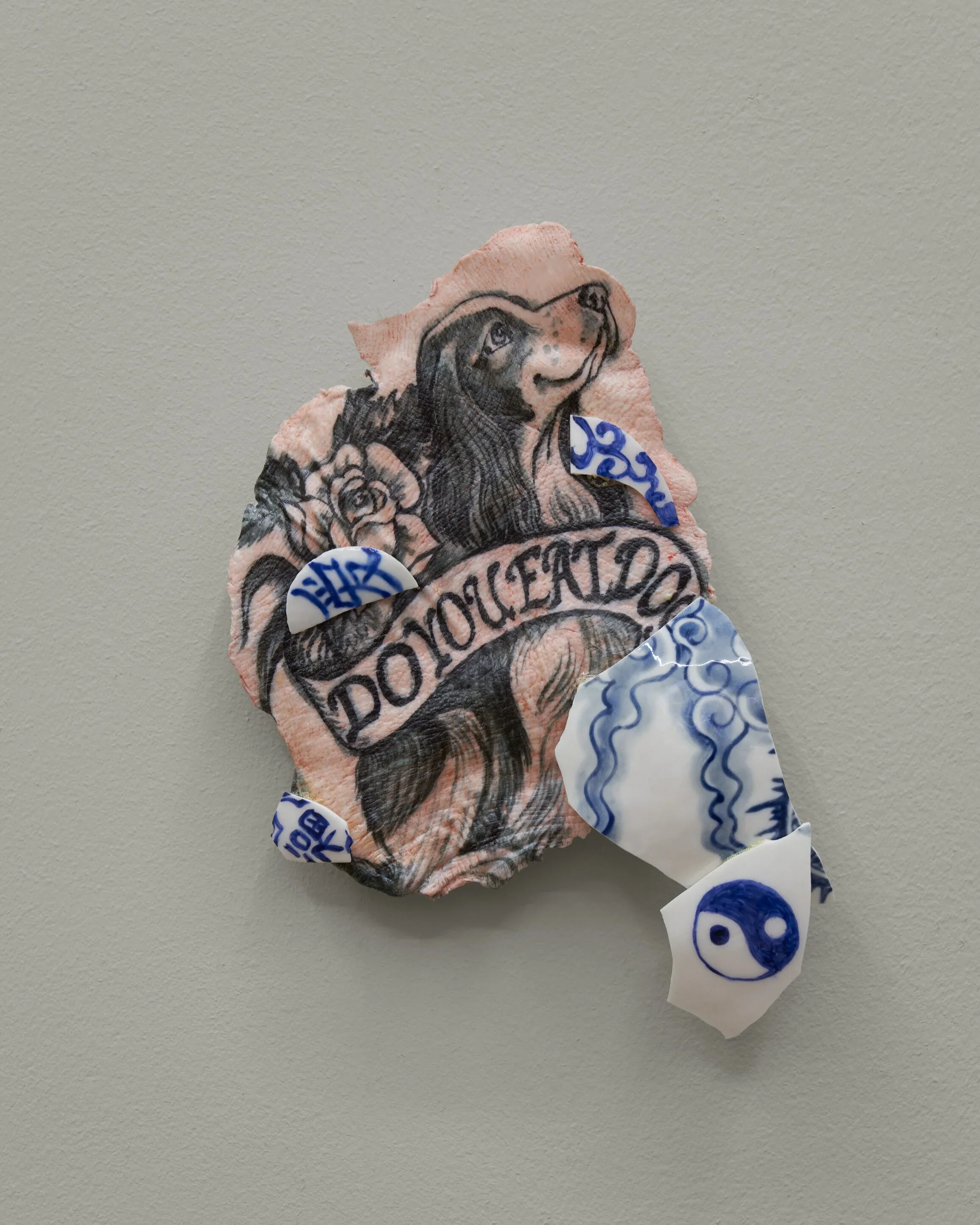

For my graduation project, I combined Chinese export porcelain with elements from European sailor tattoos. To me, export porcelain is a "neither-fish-nor-fowl" thing — made in China, but designed to satisfy Western fantasies about China. It’s not truly Chinese aesthetics at all; it was made to fulfill the Western exotic dreams. Much of it was custom-made, often with religious themes that would completely baffle a Chinese audience.

Our mutual imaginations of each other are literally painted onto blue-and-white porcelain. When Chinese artisans tried to depict Western religious scenes, you’d get something like a Jingdezhen auntie with a big nose — anatomically off in every way, but entirely sincere in its imagined depiction.

I felt this was the perfect metaphor for my own situation. The West’s imagination of the East isn’t so different — distorted but earnest. Export porcelain became my way of expressing emotions I couldn’t put into words, but felt deeply: the frustration of wanting to explain yourself, yet finding it impossible to explain clearly.

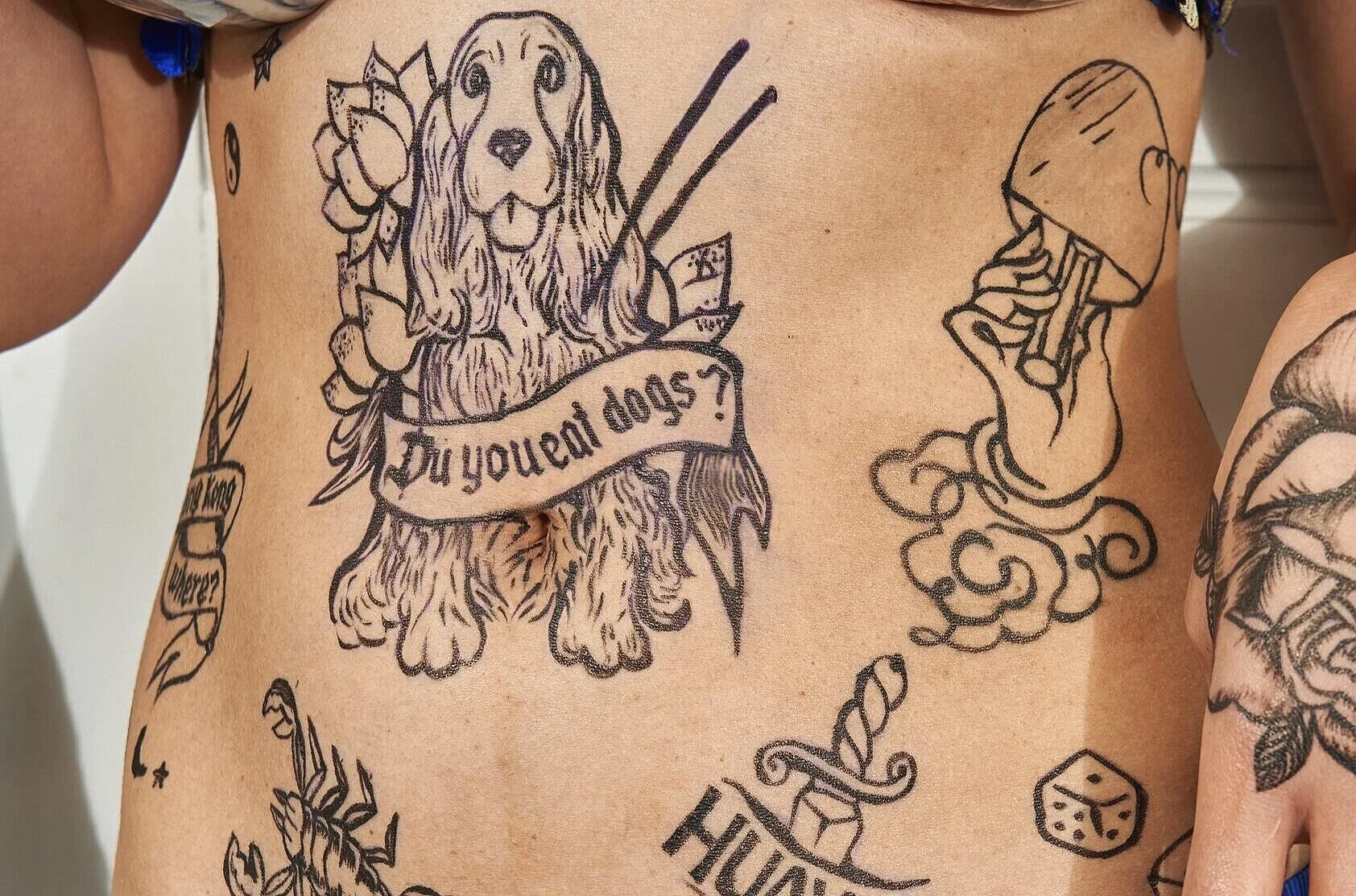

Pin-up China Girl

Q: Your work "Poster Girl" seemingly caters to Western imagination of exotic Oriental female images, but the tattoo content on your body makes me feel like you're actually using your body as a mirror, reflecting their projections back to them. It's not the traditional image of a weak figure being gazed upon and projected onto, but rather like a "femme fatale"— a seductive woman who's about to devour them, with a sense of controlling power.

I didn't think that much about it. Anyway, roughly speaking, from living here I've summarized some "three-piece sets"—these questions they ask you, these Westerners' confusion about you, their superficial understanding of China, their superficial understanding of Hong Kong and Taiwan issues. They don't even know where Hong Kong is, but they've already taken sides. I don't judge these things; I just take these thoughts they have about me—okay, fine, I'll reflect them back to you.

But that was a later thought. Going back to the export porcelain I mentioned earlier, I think export porcelain can find a point of mutual resonance and shared memory. The row of blue and white porcelain imported from China that Norwegians remember in their grandmother's house intersects with my cultural memory. Because if you're just telling so-called Chinese stories, no one will listen—it has nothing to do with their lives. Things need to have intersection points to possibly have an audience.

For me at that time, having someone listen to me was too important. I couldn't find precise language to express myself, so I could only use visual language. It was precisely because of linguistic inadequacy that visual language became more powerful.

I used Western sailor tattoos—combining their grandfathers’ tattoos with traditional Chinese blue and white porcelain, using their initial impressions of the East as an invitation to imagine the Orient.

I think when people talk about distant places, they often exaggerate. When I watch Western news, it seems like whenever they talk about news related to China, they would only pick the bad things to report. Or many also only talk about their imagined Orient through travel, not the real Orient.

“Pin-up China Girl” Tattoo Details

“Pin-up China Girl” Ceramic Props

Q: Your work has been collected by the National Museum of Norway, and you've received Norwegian craft awards. These are quite national-level awards. I don't know if such awards are only for Norwegians or if foreigners who live there long-term can also receive them? Does this give you a feeling of representing Norwegian art?

I'm actually considered a Norwegian artist because I started my career here. I studied for my master's here and received several national scholarships, so I don't have to worry about livelihood and visa issues. Norway has many scholarships supporting excellent graduates' projects and emerging artists.

I haven't finished telling you that story yet. After graduation, I had only 4,000 yuan left in my pocket. Love was gone, money was gone, studies were finished, and I had said what I wanted to say. I had put all my money into my graduation work and didn't even have enough for a plane ticket.

But by sheer luck, I won an award—roughly equivalent to 60-70% of the annual income here, given to me all at once. Because everything was in Norwegian at the time, I didn't really understand how the system worked. I desperately wanted to create my graduation work and needed to find sponsors. By accident, I applied for something without reading it carefully—it seemed like I applied for the biggest award, something like Young Artist of the Year, and suddenly this huge pot of gold came crashing down on me, so I stayed here.

Then I got scholarships every year. These scholarships are equivalent to giving you 50% of a basic income, ensuring you don't change careers and can continue making art.

Q: You graduated from China Academy of Art's sculpture department, and your sculptural foundation is clearly excellent. Your current work mainly uses ceramics—why did you choose this material? Did you choose this medium before going to Norway, or after?

In my current work, concept is most important. The concept requires me to determine which material—whether ceramics, fiber, or metal—can most precisely express it; that is the material I will use.

There’s a bit of a return to basics. In my undergraduate studies, the sculpture department had five directions: Studio 1 focused on figurative work, Studio 2 on urban themes, Studio 3 on materials—stone carving, wood carving, metal welding, and thermoforming (they didn’t call it ceramics, because ceramics was a separate department at our school), Studio 4 on conceptual work, and Studio 5 on fiber arts.

I feel I’ve returned more to the sculpture department now. I think ceramics is just a material. Back then, it might have reflected my personality—I was rather melancholy and sentimental. Our advisor would mention Jingdezhen, saying my work was very suitable for porcelain because porcelain is quite fragile.

As it turned out, porcelain cured my melancholy. Because it is so difficult to work with, I could only become stronger. In the end, I've completely transformed—now I'm not melancholy at all; I've become very tough.

Still Life - 24th of February - 27th of March 2022

Q: You seem to frequently return to Jingdezhen to create. Are your works mainly completed by yourself alone, or do you go to Jingdezhen to find masters or assistants to help?

It's more about the work directing where I go. Everything serves the accuracy of conceptual expression and precision of artistic language. I think if I can find usable alternative materials, I try not to use porcelain because porcelain is too difficult to work with. I'll use copper if I can. But if I've determined that I want to do this project and the concept absolutely requires porcelain, and this material is irreplaceable, then I will use porcelain.

If something is suitable to be made in Jingdezhen, I'll go to Jingdezhen to make it. If a work is hand-pinched or directly hammered out, I might make it in Europe. Jingdezhen is more suitable for mass production, works that are slip-cast and then assembled. For sculpture, it might be more suitable to make in Europe or places other than Jingdezhen, because the clay is easier to work with.

Q: Is your creation more concept-driven? Do you have an idea first, think through all the details, draw sketches, then execute? Or is it more organic, developing ideas gradually while making?

I think these two complement each other; neither is most important. I'm relatively more concept-driven, but craftsmanship is also very important because sometimes when you're unconsciously sharpening knives, sharpening pencils, or randomly pinching clay, inspiration might emerge.

My current practice is divided into two parts: one is commissioned public art projects, and the other is my own work. I'm constantly learning to balance the proportion and intensity of these two sides, because raising two children definitely requires different attention than raising one child, so I'm also learning about this.

Generally speaking, commissioned work still requires sketches to come out first. Sketches need to be very specific. Evan required architects to build models and do rendering, it's more like doing an architectural project. Because it's extremely rational and you must ensure everything is reliable.

But when it comes to gallery or museum work, it's relatively more free-spirited. Sometimes you suddenly get an inspiration with a "snap," sometimes you get an inspiration while randomly drawing. I think sometimes it’s 60/40, sometimes 40/60—the methods are different. Many people just randomly pinch clay, very respectful of their stream of consciousness.

We Come From the Other Side, Mezzanine Gallery, United Nations Office Geneva, Switzerland.

Q: What's your daily schedule and time allocation like these days?

Every day I'm struggling between a healthy lifestyle and an artist's soul—the struggle between Dionysian and Apollonian spirits. If you're too rational, your work lacks passion; if you're too passionate, you die early. I argue with myself 800 times a day.

I think I can only now have a rough life distribution map. My life is a tale of two cities—half in Europe, half in Jingdezhen. I spend a bit more time in Europe. My life structure is identical: I have an apartment and a studio in Oslo, Europe, and an apartment and a studio in Jingdezhen.

Sometimes when I'm busy, it's completely chaotic. If you're an athlete, there are seasons and off-seasons—during the season, you train intensively. When things are tight, I'm extremely busy with almost no social time.

For example, last time I used 2 months to complete 4 projects, and there were family issues—my father fell ill, so I went home twice. Every day from 8:30 AM to midnight or 1 AM, the intensity was enormous. I directed assistants and masters every day, operating at the limit to complete 4 projects. Afterwards, I completely collapsed when I returned. I did nothing all summer, took a month off, did absolutely nothing—didn't even read a book. Just camping and swimming. Now I feel very guilty. I want to reform and work hard. I feel most secure when I'm working.

Q: You should be preparing for your September exhibition in New York now, right?

Yes, I'm extremely busy now, both nervous and excited. I'm also very curious about how New York audiences will respond to my work.

Still Life - 24th of February - 27th of March 2022 details

Q: Are the parts that look like meat in your works also made of ceramics? They look so realistic—how exactly did you make them? It's amazing.

That's one of my experimental projects. When I was making those meat jars, my techniques had really matured. I had already mastered it and became quite familiar with it.

Those jars in my solo exhibition were more like samples—they're not perfect, but very real, very explosive.

Because in Jingdezhen, everything is made very perfectly. When I made those works with torn skin and exposed flesh, I felt very uncomfortable, thinking I could make them more perfect. But my friend said, "You're crazy, it's very rock and roll."

“Pin-up China Girl” Ceramic Details

Q: I think it's technically brilliant. Conceptually, how did you think of combining meat with blue and white porcelain?

Actually, it's one of my art projects that I've been researching up to this point. It more or less reflects my current state of being—as an immigrant with a deep-rooted Chinese mentality, facing cultural shock in a foreign country and adapting to new living circumstances. Whether intentionally or unintentionally, you shed part of your identity, shed a layer of skin, and then grow new skin.

I feel I'm in a state where my old Chinese skin is still shedding, but the new Western skin hasn't grown yet—a rather vulnerable state. Now I’m in a sandwich situation—neither fully Chinese nor fully Western, unable to return completely to either side.

It's a molting state, a process of having to choose between old and new identity. Just like getting a tattoo as an adult—you have to make a choice. You have to accept part of the so-called Western concepts and traditions, while simultaneously discarding part of the old Chinese traditions—and it’s not just about daily choices like food or lifestyle.

I think this is a transitional period. I find it fascinating, vulnerable yet fascinating. It's particularly painful and uncomfortable, but at the same time very vital, because it's a rebirth, the labor pains of repeated births.

As for porcelain, blue and white porcelain is my mother tongue. A jar is a body—it can quite well express this feeling I can't describe. It's also very imperfect, but perhaps truthfully reflects my current state.

Bunad Tattoo Shop Installation Ceramic Details

Q: I think this background and conceptual explanation make the work even more impactful. You mentioned the creative inspiration—vases as bodies, the porcelain surface as skin, and that if you strip away skin color and appearance, everyone has the same flesh and blood underneath. Combined with your discussion of cultural influence and the pain of identity transformation, the result is incredible.

This feeling is indescribable with words, and others can't experience it either. I feel it because we share common experiences as Asian women, as first-generation immigrants—we have similar experiences and circumstances. I think if you tell this to others, they won't listen or resonate. You can only find a visual language that might make others willing to listen to your story.

Q: There are many Asian ceramic artists in America who also use blue and white porcelain elements and symbols in their work. Many people see this as a cultural connection—choosing an element from the culture they come from to connect with their identity and represent their culture.

But your starting point seems different. I saw you in a video interview talking about how you researched the evolutionary history of blue and white porcelain through trade from China to the West. Could you talk about your understanding of blue and white porcelain history? And what does choosing blue and white porcelain as an element mean to you?

I think this goes back to our discussion about whether technique comes first or concept comes first. I probably lean more toward concept first—I want to express something, so I search for the most suitable language, which is how I found blue and white porcelain.

If you trace the history of blue and white porcelain, you can almost connect modern global history, modern trade history, and China's modern history. If you follow blue and white porcelain along the Silk Road, along the Maritime Silk Road, you'll discover many historical intersection points. By tracing these histories and using history as a mirror, you can better understand your contemporary life, including living in a foreign land. For me, this might be a way to grasp things.

From another perspective, it’s like the Chinese poem that says, ‘One cannot recognize the true face of Mount Lu because one is standing on the mountain itself.’ When you’re in your homeland, you might think these cultural totems are just boring symbols, and instead prefer to pursue symbols from Berlin or New York.

But if you leave that place and go to the other side of the river, the other side of the sea, you might see the mountain's outline. You might increasingly develop a sense of identification with these visual symbols. Blue and white, or dragon motifs in blue and white, might best represent the Chinese spiritual temperament—not just a symbol, but a deeper spiritual connection that you might resonate with. It's like going to Rome and seeing the Colosseum, feeling it's the cradle of European civilization.

Q: I understand that you seem to be using blue and white porcelain as a medium to express that people all over the world are actually connected, that people are not isolated islands.

Yes, no one is an isolated island. This so-called ‘where I come from’—or the idea that something sprouted from the ground and belongs completely to me—I don’t think that’s so absolute.

Q: I see that in America, many Chinese Americans who use blue-and-white porcelain have the attitude: ‘This is my culture; people from other cultures cannot appropriate my elements.’ But if you understand the history of blue-and-white porcelain, you’ll discover that the cobalt used to paint it originally came from the Middle East—China didn’t have it initially.

Sumali blue—originally this blue came from the Middle East, from Iran.

Q: And this blue is actually related to their Islamic religious beliefs, right?

Yes, and intricate patterns like tangled lotus, which aren't really native Chinese aesthetics but derive from the Middle East's complex religious miniature paintings. Very likely, Chinese ceramic craftsmen received some of their orders, found them quite beautiful, and gradually incorporated local elements, evolving into different floral patterns.

If you trace it back, you can go as far back as ancient Rome. During Alexander the Great's eastern expedition in ancient Greek times, he brought some pan-Hellenistic influences to the Middle East, which were then brought from the Middle East to China.

It's very interesting—if you investigate carefully, you can connect the entire world history. Scrolling lotus patterns were continuously localized, continuously absorbed by local cultures. For example, our Chinese scrolling lotus usually features peony and lotus flower patterns, but there are also vines on the pedestals under Greek statues. We localized the plants, turning them into peonies or lotus flowers. Then European merchants came, saw Chinese porcelain as beautiful, and shipped it to Europe. Europeans thought this was exotic Orient, so there were many misunderstandings. Actually, human civilizations often borrow from and inspire each other.

Q: I think when tracing cultural origins and investigating cultural identity, the question is: where do we stop? Blue-and-white porcelain seems to represent Chinese elements to people of our generation. But this traces back to the Yuan Dynasty, when the Mongol conquest of the Song Dynasty opened up new trade routes that brought Middle Eastern cobalt materials and techniques to China, eventually leading to the development of blue and white porcelain in places like Jingdezhen. But Chinese history is much longer than the Yuan—the Song Dynasty had no blue-and-white porcelain, and earlier dynasties before the Song had none either.

The spread of blue-and-white porcelain abroad, which made foreigners aware of it, seems closely tied to the foreign trade that began in the Ming Dynasty. Western understanding of blue-and-white as a Chinese symbol mainly emerged after the Ming Dynasty started maritime trade, when it was exported as a commercial product.

Yes, I think going back to your original question about why I chose blue and white—I think people are more interested in things related to themselves.

I think I tarted tracing my own history only after arriving in Norway, or after living in the West. Why should I learn perspective, anatomy, and a series of Western aesthetics? Because I was in the sculpture department, so my aesthetic was shaped by ancient Greek aesthetics. Why are the Prince Charmings in my imagination all Western Disney-style Prince Charmings, or long-haired princes with severed heads from Western religious paintings? Why is this? I don't understand.

What shaped me? I traced the blue-and-white thread and found Western exploration, the Age of Great Navigation, the rise of the West and the decline of the East—all the way to the Macartney Embassy visiting Qing Emperor Qianlong and being rebuffed, later leading to the Opium Wars, which opened the door to modern Chinese history. From there came China’s continued experience of humiliation, and the resulting Western dominance in culture and economics. Why look up to the West? Why be attracted to it? Why are Western welfare and other systems considered better than ours? Where does this come from? I really want to understand, because ultimately, people are always interested in their origins.

Denmark, Holland, even America across the Atlantic—all have a fascination with blue-and-white porcelain. This fascination often centers on a kind of feminine beauty, which is frequently associated with the East, though I don’t know why. People seem drawn to destroy or conquer things that are weak, fragile, and beautiful. I’m curious about my own circumstances and want to get to the bottom of things.

Also interesting is that China is now rising. China's cultural output and contemporary China's foreign image are slowly being established. I find it fascinating to catch this era, watching the world change at such rapid speed, watching the world change before our eyes.

Details from Lin Wang’s Solo Exhibition 2019 at The Vigeland Museet

Q: I think you're very self-reflective while also sensing how people around you see you, and you reflect on the influence of others' gazes on you. As a Chinese person living in the West, you're also studying the relationship of mutual observation, understanding, or misunderstanding between East and West. I find this perspective switching very interesting. You have a long-term project called "Exotic dreams and poetic misunderstandings." Can you introduce the origin of this project?

Yes, I think I have a very good mutually growing relationship with my research project. Actually, if I had always stayed in China, I definitely wouldn't have made such works. This project and I grow together. When I have thoughts and confusions I can't express, I make a work. This work helps me throw the question to the outside world, then gives me feedback, and this feedback creates who I am now. I might be molting now, so my work also feels painful.

Q: Is it more painful than when you first started? What's the main source of pain now?

I'm considered a Norwegian artist, but I’m also authentically Chinese. The longer I stay in the Nordic countries, the more I feel I become like a Shandong woman. All that Shandong influence seeps out unconsciously from my subconscious—I don’t know why.

For example, taking summer vacation. For Norwegians, this has been their way of life since childhood, but for me, it’s very difficult. If I were more hedonistic, or younger like the post-90s or post-00s generation, I might not be so hard on myself.

I found not only am I like this—a Hong Kong girl I know here feels the same way. I think someone from North America would probably feel as uncomfortable. But locals wouldn't feel this way. If we foreigners didn't appear, they might think the whole world should be like this. But later I discovered, if you really live in the Nordic region, really take root there, you'll understand why they must have a month of summer vacation, because the entire bitter cold winter is too long—half the year is ice and snow.

Without this summer vacation as beautiful as a heavenly dream, without giving everyone a break, I think people couldn't bear it. Different geography and climate of each place influences locals' worldview.

Q: That makes a lot of sense. We usually think their relaxed attitude comes from high welfare, but in reality, humans are often like animals and plants—deeply influenced by their environment.

Yes, for example, Norway—when you open the door, there are fjords and seas. Their thinking and ideology are shaped by these landscapes, climate, and geography, so they see many things as natural.

We Chinese people are similar—we believe we should buy houses, save money, and work hard every day. Then we look at each other disapprovingly, thinking, ‘You should follow my rules.’ Actually, having people like us shuttling between both sides in the middle zone is quite beneficial—we can communicate and understand each other better.

Q: Have you thought about exhibiting in China? Do you think the same works would receive different feedback if exhibited domestically?

I don't know, I know nothing about the domestic scene. Because I've been quite fortunate these past few years—I'm quite a busy artist here, always having projects, whether public projects or exhibitions, always extremely busy. Almost too busy to handle.

If there were invitations from China, I think I'd definitely make different works—I'd have to think about how to dialogue with domestic audiences. Because I've always lived in Europe, exhibited in Europe, my audiences are all Westerners. I have to find language they can understand to communicate with them.

Q: Will you also consider American audiences for your exhibition in New York?

I don't want to. If you consider others, there will always be people who like you and people who don't—you might as well just be yourself.

Bunad Tattoo Shop Installation- The National Museum-Skakke Folkedrakter

Q: You've mentioned several times your identity as a Shandong woman. As the hometown of Confucius, would the Confucian patriarchal traditional Chinese cultural influence be even stronger in Shandong?

Much stronger in Shandong, absolutely stronger. In my era, rural women still didn't sit at the table. Men had one table, women another. Now it might be better.

Q: Even within your own culture, as a woman, you seem to occupy the position of the ‘other’ and a marginalized group. Therefore, you examine the power structures around you and your own identity within this environment. This is similar to your experience as an Asian or outsider entering a new Western environment, where you examine and respond to the gaze of others.

Shandong is a very male chauvinist society. Even now there are still many remnants of following the "three obediences and four virtues." I felt particularly uncomfortable there at the time, but I couldn't articulate it because everyone around me was like that. When you haven't stepped outside, you might not realize these things are wrong. So again, it's "not recognizing the true face of Mount Lu because you're within the mountain."

On the other hand, Shandong people also have admirable virtues—they are righteous and hospitable. When I cook, it’s always big plates with food piled high to fill you up. This is very different from my current life. For example, when I go out to eat now, French style cuisine comes on a big plate with just a tiny bit of food in the middle—it’s an extremely stark contrast.

I remember when I went to study in Hangzhou, I was very surprised. I remember Shandong breakfast—we ate a bundle of youtiao (fried dough sticks), a whole steamer of baozi (steamed buns), while my Hangzhou or Shanghai classmates had one vegetable bun and one youtiao. I found this very devastating and surprising. Then when I returned home to eat, the portions of our dishes were so large, and good restaurant standards were fried meat piled into a point that could touch your nose tip, but southern dishes were very small, very delicate.

Then I had this feeling of unresolved resentment, always this feeling of unresolved resentment. The society I live in now is quite refined. I can't just be very straightforward anymore—charge you 10 yuan and give you a big bowl of food, using those Shandong woman tactics.

But I have this thing in my bones, which is very uncomfortable. Whenever I host guests, I make too much food. Then I think, forget it, let it be this way—it's also a characteristic.

Q: You've reconciled with this tangled and contradictory psychological state, accepting that this is who you are.

I think it's a continuous process of adjustment. I think my projects are the same—I haven't yielded to any, haven't been disciplined by any.

So I'm in a skin-splitting molting process now. Because deep down I want to serve a big plate of stir-fried chicken, or a plate of ribs, a plate of sweet and sour pork, but my budget and context require me to serve a plate of French cuisine. So I'm always in pain—whether to be myself or conform to local customs is a quite conflicting issue. So I just gave up and became darkly humorous.

Performance Dinner at KODE.4 Museum (2018)

Performance Dinner at KODE.4 Museum (2018) details

Q: You created a feast using ceramics, with blood-red wine flowing from fountains. That work looked quite refined while also being grand. What was the opportunity and idea behind creating that work?

That’s perhaps our Shandong women’s tactic—our buns are served in such big plates. That was a kind of surrender to my nature, a satisfaction.

Because after graduation I stayed in Norway as an artist. But I was very lonely then, extremely lonely. I had already broken up with my ex, though that was just a secondary factor. But as an artist, you often face piles of clay and the studio alone. You don't have that daily commuting rhythm. You need to solve and dissolve this situation—you need deep friendships, you need to arrange your life to a so-called normal person's level.

I felt my works at that time were all solving my problems. I desperately needed friends, I needed a team. If I was just making sculptures, I didn't have a team. Why not invite everyone to eat, using the most simple method? I'd make dumplings, then invite everyone to come to a dinner party. Making a dinner party, I'd need a bunch of people to coordinate with me. I'd have to make contact, force myself into an open state, and connect with all kinds of people. Contact museums, contact retired sailors to sing sea shanties, contact chefs, or contact immigrants. It was a very painful process of pushing myself out, and I'm actually a very introverted person—though it might not show—but it was a very necessary self-rescue process, using artwork to socialize and connect with the outside world, to interact, rather than being in a stagnant state. And it really worked, but it was a very painful process—painful yet joyful.

Performance Dinner at KODE.4 Museum (2018) details

Q: I think the difficult part is that an artist's creation needs to dialogue with culture. When you change cultural soil, you have to find new points of dialogue and ways to connect. There's definitely a long, difficult process in between. But I think you're doing great. Like you said, you don't surrender to either side, which makes your self become stronger, like a tree continuously growing upward.

But I feel I'm always solving problems. I didn’t think about cultural dialogue—I can't think that much. In the beginning, I just wanted to make a lamp, wanted not to be depressed during the polar night. I've just been solving my own problems. I think summarizing these cultural dialogues, including these interviews—many things are only understood in hindsight.

Now when I look back at the path I've traveled, I can make a rough judgment and perhaps respond to your interview, roughly saying something. But many artists' early works are non-rational—they come from intuition. Through my work, I'm just always solving my contemporary problems.

I feel my life is full of unpredictable challenges. I think about how to bring some peace and clarity all day—whether through painting my walls bright or through artworks, just to make my life slightly better. That's all.

Q: And you might really need these problems—without problems, there might be no inspiration.

I've already thought about it. If I have no problems, I'll become a peaceful, idyllic artist. I'll arrange flowers, drink tea, and make some beautiful things—I can do that too.

This interview was originally conducted via Zoom in Chinese on August 5, 2025 by Zou Chen, Los Angeles/Oslo.